This post, from Don Linn, originally appeared on the Digital Book World blog on 11/2/09, and is reprinted here in its entirety with his permission.

One of the matters much on my mind recently has been retail book prices for both electronic and print editions. I’ve been knocking the subject around for several months, partially due to the ongoing clamor for free or cheap long-form content (spotlighted most brightly by Chris Anderson’s FREE), partially due to an aborted personal foray into digital publishing, and most recently due to the retail price war currently underway among Amazon, Wal-Mart, Target, Sears and others, where prices of hardcover bestsellers (not remainders) have been pushed below $9.00.

That’s below the retailers’ purchase price in most instances and is clearly unsustainable over time (if not illegal, as the ABA has alleged).

Many have cheered lower prices as a way to grow readership and entice readers to purchase more books (both E and P). After all, readers are getting great deals and publishers (so far) are still getting paid on standard discount schedules. Others have taken a more nuanced look and have written about the consequences of sharply lower prices and ‘de-valuing’ content over time. Bob Miller, Publisher at Harper Studio, describes brilliantly the ‘roadkill’ attendant to deep-deep discounting in “How Much Should Books Cost?“

While I take a back seat to no one in arguing that publishers owe it to readers to provide books in all formats at reasonable prices (e.g., in most cases maintaining print prices on digital books is borderline insulting) and that the customer ultimately drives the business, it’s important to remember that publishers have another set of customers who are in play and upon whom they are equally dependent.

Those customers are called authors and creators and we need to balance their economic realities with those of readers.

Let’s be clear. In most cases, the days of monstrous advances are over. Publishers can’t afford them and the few superstar authors who can command them will at some point recognize their ability to self-publish and distribute far more profitably (and quickly) than their current publishers can. Stephen King is a brand. Nora Roberts is a brand. They don’t need a publisher’s imprimatur or antiquated logistics to sell truckloads of books. Those folks will be fine.

By the same token, writers who do not rely exclusively on income to pay the bills can also self-publish. Tools and services are readily available and mostly easy to use so that the aphorism, “We’re all publishers,” is true. Some will use self-publishing as a stepping stone to more traditional publishing. Others will master it and create work comparable to the best traditional publishing has to offer. A thousand flowers will bloom.

The publishers’ author/customers I worry about are those who fall between these two groups. They are the people who write for a living and who bring us the workhorse books in their categories (from literary fiction to genre fiction to all manner of non-fiction). Their advances have historically been relatively low and their sales relatively modest. They write for major publishers and independents. They write books that backlist and, in a small but very important number, they write really important books that either break out commercially, or say something significant that might not otherwise get said.

We need these writers and a significant component of a publishers’ role is to sustain, encourage and build their careers. When content’s price and value is pushed below a sustainable level for publishers, these writers will suffer. They will be forced to make the economic choice to write less to finance their careers. It’s not enough to say glibly that ‘writers have to write so they will’ or that self-publishing will be their salvation.

When content’s value drops, self-published content’s value drops as well.

We can develop new advance and royalty schemes, profit sharing payments for authors and other ways to carve up receipts from book sales among booksellers, publishers, agents, and creators. MacMillan this week announced a new boilerplate contract pushing author royalties on digital publications still lower. The sad truth is, from the author’s perspective, if the per unit receipts are low enough, it almost doesn’t matter what the split works out to be.

Kirk Biglione wrote recently on another topic that (I paraphrase) ‘in a digital world consumers get what they want.’ At the moment, it seems readers only want lower prices. My hope is that deep-discounting retailers will recognize that books aren’t a product that can be readily substituted with lower-cost imports like many of the products they stock. My further hope is that consumers who demand ever-lower pricing on intellectual property will begin to think beyond the next book they want to buy.

At this moment, I’m not optimistic about either.

Don Linn has a sordid past as a mergers and acquisitions investment banker; cotton and catfish farmer in deepest Mississippi; book distributor (as owner/CEO of Consortium Book Sales & Distribution); publisher (The Taunton Press); serial entrepreneur and general ne’er-do-well. He was a founder of the late Quartet Press and is currently an investor in OR Books, while consulting with and advising other publishing entities. He’s a graduate of Harvard Business School and Vanderbilt University, and is endlessly fascinated with the convergence of technologies with media and the opportunities and business models arising from their collision.

Learn

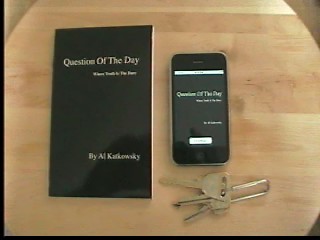

Learn Question of the Day began life as a simple, workplace pastime. Al would pose a question to co-workers, providing fodder for discussion. Eventually someone suggested Al turn his questions into a book, and he did, classifying them on a scale of “Light” to “Heavy” based on how serious or easygoing each question is. Once the manuscript was finished, he spent about a year querying on it. He received a lot of encouragement but no offers, and started thinking about alternative routes to reaching a readership.

Question of the Day began life as a simple, workplace pastime. Al would pose a question to co-workers, providing fodder for discussion. Eventually someone suggested Al turn his questions into a book, and he did, classifying them on a scale of “Light” to “Heavy” based on how serious or easygoing each question is. Once the manuscript was finished, he spent about a year querying on it. He received a lot of encouragement but no offers, and started thinking about alternative routes to reaching a readership.

Here are some tips based on my personal experience. Just make sure you’ve got a large coffee ready – and make your book happen!

Here are some tips based on my personal experience. Just make sure you’ve got a large coffee ready – and make your book happen! After working on a computer everyday for more than 25 years, I usually feel pretty confident tackling software issues. I’m a real, nuts and bolts kind of guy anyway, so fixing whatever comes up is really second nature for me.

After working on a computer everyday for more than 25 years, I usually feel pretty confident tackling software issues. I’m a real, nuts and bolts kind of guy anyway, so fixing whatever comes up is really second nature for me.