Today we continue Mark Barrett’s series on theme, which originally appeared on his Ditchwalk site and is reprinted here in its entirety with his permission. You can read the first entry in the series, ‘Axing Theme’, here, and the second installment, Thinking Theme For Fun and Profit, here.

On Monday I introduced you to Thomas McCormack and his devastating critique of the way theme is taught. On Tuesday I talked about how emphasizing theme and ‘important’ literary works actually discourages some (if not many) students from reading and learning. A helpful reader provided more ammunition in the comments.

The consistent theme in these arguments is that theme should not be deployed as an analytical tool. Readers, students and teachers have more insightful measures by which to judge literature and writing — a sampling of which awaits you in the conclusion of Mr. McCormack’s document. Too, at the highest levels of academia criticism is always in flux, meaning determinations of theme are not simply potentially speculative but inherently transitory.

In short, using theme to reveal meaning in a story is like using divining rods to discover water underground. Many people swear by it, but it has no basis in fact. Theme as a creative technique, however, can be a powerful means of organizing and expressing ideas. By understanding theme in this context we not only learn how to use it appropriately, but also gain insight into why theme is poorly taught, and how theme can be so easily turned to nefarious purposes. (A subject I’ll tackle tomorrow.)

Now, suppose you and I are going to build a house, a car, or almost anything you can think of. In our collaboration we will have functional requirements to discover (it must not blow up, it must turn on when you press a button), we will have usability requirements (it must not be confusing, it should provide positive feedback when operated), and we will have aesthetic requirements (it should be cool, sexy, retro, whatever.) Unfortunately, completing these design tasks only reveals two new obstacles. First, there are a lot of requirements to organize. Second, there is no inherent consistency to the requirements.

For example, if we’re making an outdoor grill we could satisfy our aesthetic requirements by putting different stickers or paints on the same functional model. Or we could make different functional models with varying capacity and burners, yet present all models with a common paint scheme. Or we could emphasize usability and give everyone a Model-T grill: basic and black. We might even decide which choices to make based on a set of priorities, but that would only kick the can down the road. How do we know what our priorities should be?

The answer, as you might imagine, is to employ theme as an editorial tool to help determine which requirements to keep or emphasize, and which to omit or diminish in importance. But even here we need to be careful, because all themes are not equal. Proportionality in theme is also critical to our ability to integrate theme in any instance.

For example, it would be tricky to make an outdoor grill based on a theme such as ‘war is hell.’ I’m not saying it couldn’t be done, but the end result would probably be so obvious as to make it no longer a war-is-hell grill but a statement in which the theme detached from the object. Yes, the grill might function as a grill, and particularly so as a conversation piece (hold that thought for tomorrow), but the theme would exist apart from the grill’s functionality. Meaning we could just junk the grill and go with the message, or vice versa.

(Note that this is exactly what happens when a student proposes a theme that seems preachy relative to the story being analyzed. The student goes too far in trying to find deeper meaning and ends up under hot lights, accused of moralizing. When an author writes a preachy story the same dynamic is at work. In such instances theme — meaning a message the writer is trying to communicate — separates from the story. The end result is that story dies at the hand of theme. And yes, you should consider that a cautionary tale.)

Scaling our thematic grill goals back, then, we could probably embrace themes like ‘the future,’ ‘masculinity,’ or even ‘heat’ in a way that allowed us to harmonize the elements of our grill without beating cooks over the head with a message. (It’s not that we’re trying to hide our theme per se, just that we don’t want it to separate from the object.)

In picking the theme for our grill we could simply make one up, but we are not obligated to conjure out of thin air. For more focused inspiration we could look to the intent of our object (cooking), or to knowledge about people who might want to experience or use that object. Because we are making a grill, and because we intend to sell it, we might distill marketing data about grill sales into a generic customer profile: male, mid-forties, overweight, meat-eating, stubble-faced, beer-can-crushing, etc. This profile, in turn, might suggest a variety of possible themes that could be used to harmonize our grill requirements.

If we chose ‘masculinity,’ for example, that one word and its attendant (real or imagined) traits would become both a filter and editorial point of focus. Each part on the grill could be shaped and machined to look burly. We could also comb through our usability and functionality requirements and make thematic choices there: eliminate a few conveniences to make the grill seem more rugged (and save on manufacturing costs); engineer the grill’s functionality to require more muscle (firm detents on the burner knobs, a heavy lid).

Ideally, at the end of the design and manufacturing process, our theme would be indistinguishable from the final product even though it informed every aspect of that product. We would not want someone looking at our grill to see our theme standing apart because that would mean we failed to integrate and harmonize our requirements. (In that case, again, we could have saved ourselves the trouble and simply put up a sign.)

Yet this is exactly what students are asked to do with stories. It should also be clear from this example that the easier it is for a student to identify a theme, the more likely it is that integration of theme into story was bungled. Ideally, integration of theme in a fictional work should be indistinguishable from the work itself, yet students are routinely told that they should be able to make such distinctions.

(It is possible for thematic obviousness to be a marketing goal in itself. A line of light-weight Cute Tools in various shades of pink would be a fairly obvious appeal to cultural norms of femininity. It is also possible for thematic obviousness to be an artistic goal, as demonstrated in the works of Andy Warhol. It is not, however, possible for thematic obviousness to be a storytelling goal because storytelling requires suspension of disbelief, where thematic obviousness destroys suspension of disbelief. Again: bad storytelling makes theme apparent while good storytelling makes it organic to the whole — yet students are routinely told that being able to identify a theme is central to being able to appreciate the best literature.)

Earlier I suggested one of the things we might do, short of harmonizing our imaginary products thematically, would be to paint them all the same. Readers steeped in marketing may have noticed that this projected our grill-making operation into the realm of branding. Not surprisingly, it’s possible to inject theme into branding, just as we used it to help organize the product requirements for our grill.

In fact, it could be argued that branding in its purest form equals theme at its most abstract. If our product line is widely varied — say, appealing to beer-can-crushing goons as well as more genteel shoppers — specific themes may actually thwart our objective (sales). Acting as both a filter and editorial tool, theme in the guise of branding can be used to unify elements of our business and products such as color, type style and logo design, which will in turn inform all resulting advertising in all media.

In instances where a product line is more focused, theme as branding can be extended to the look and feel of objects, and I think Apple is a good example of this. I can’t tell you what the theme of Apple’s products is — it may or may not have been articulated in-house — but when I see an Apple product I see it as thematically connected to other Apple products, which reinforces Apple’s branding. Even Apple’s preference for look and feel over usability is thematic: control systems that are unintuitive for novices ultimately provide a deeper sense of community and mastery as users becomes more familiar with them.

In these examples we can also see that theme as a technique owes nothing to sophisticated language, deeper meaning or valuation. Theme is quite happy to operate apart from concerns about worth, merit, the human condition or anything else we might want to saddle it with. This doesn’t mean we can’t employ theme in these ways, just that these are not inherent aspects of theme as a technique.

Which brings us back to storytelling and literature. As I said in my first post on theme, I gave up chasing art for something more useful to me as a writer: craft. By extension, viewing stories as machines that are made up of parts and subsystems which function to create specific intended effects means there’s little difference between our grill-making venture and any story I chose to write.

In the same way that theme can be used to edit and filter the requirements and components of our grill, we can employ theme in storytelling. But note: this does not alter theme in the least. Theme is not suddenly more important or powerful in fiction than it is when used in grill-making or branding. Theme is theme. It is a tool of creation and it is used in the same way in all instances: to filter and edit and harmonize.

For example, let’s say our grill business falters. You go back to what you were doing, I slink off to a shabby one-room hovel situated beside a polluted waterway. Night after cockroach-infested night goes by until the last lightbulb fails. I can’t eat. I can’t sleep for fear of being eaten. I am in agony.

Fortune smiles on me, however, when a typewriter and 500 sheets of 20-pound paper fall out of a passing truck. Seized by a desire I cannot name I set to work, determined to tell my story. Maybe it’s fiction, maybe it’s non-fiction, maybe it’s the stuff that guy and Oprah had to apologize for. It doesn’t matter. All I know is it’s ultimately going to be about one thing: pain.

That’s how complicated (not) theme is as a storytelling technique. Every word, every scene, every aspect of what happened in my document can be filtered and edited by one over-arching thematic point of reference — yet this says nothing about the subject matter or the facts or the events I might choose to portray.

(The previously-mentioned requirement of thematic proportionality doesn’t just apply to grills. If you are determined to write a story based around the theme that war is hell, you pretty much know going in that you’re going to have to show a lot of war and a lot of hell. War-is-hell short stories, to say nothing of war-is-hell flash fiction, usually end up about as convincing as a war-is-hell grill. Then again, if you’re going to include a lot of war and a lot of hell, to what extent does adopting war-is-hell as a theme impact the final product? The answer is that it doesn’t because you’re simply replicating the subject matter. Writing a war-is-hell story with a war-is-hell theme is as helpful as designing a grill with a grill theme. The first conclusion you should draw here is that theme should vary in some way from the object it relates to. The second conclusion you should draw is that asking a student to elicit the theme of a war-is-hell story is pointless.)

To continue the example, imagine that what I write gets published, pipelined into schools, force-fed to students, then analyzed by students and teachers alike. What are the odds that any of those down-steam analysts are going to figure out my theme, particularly if it varies from the subject matter? And to what extent is what I wrote even reducible to the original theme? Is my story, loaded with characters and events, really only pain? If so, why did I put all that other stuff in there? Why didn’t I just write PAIN on a single piece of paper? Or make PAIN posters and put them up all over town? More importantly, why didn’t I skip writing the story altogether and deal with my pain?

The question is: If pain is my theme, is pain the meaning of my story?

The answer is: No.

Pain as theme is simply one tool I use to shape the end product, just as character selection, setting, dialogue and every other aspect of storytelling should conspire to create a whole. The blindingly obvious proof of this is that I can neglect theme entirely as an author and still complete my project. I don’t even need pain as a theme in order to write about pain.

If you haven’t read Thomas McCormack’s essay, I urge you to do so. You’ll see clearly how theme as an analytical tool foisted on students is entirely misplaced, while theme as an editorial tool used by authors makes sense.

In the same way that a compass can tell you where you’re going, but not where I have been, theme seems only genuinely useful to the person employing it.

Mark Barrett has been a professional freelance writer and storyteller for over twenty years, and also works in the interactive entertainment industry.

This is a general, rambling comment covering some of the more touchy-feely components of setting up a marketing plan. I prefer a more organic approach rather than the nice, crisp document with all the numbers in a row. They have their place, but if you have an interest in developing your ability to perceive your market better, read on…

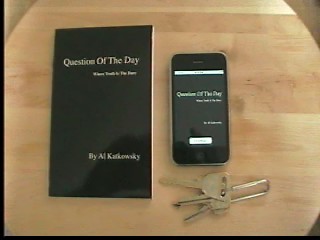

This is a general, rambling comment covering some of the more touchy-feely components of setting up a marketing plan. I prefer a more organic approach rather than the nice, crisp document with all the numbers in a row. They have their place, but if you have an interest in developing your ability to perceive your market better, read on… Question of the Day began life as a simple, workplace pastime. Al would pose a question to co-workers, providing fodder for discussion. Eventually someone suggested Al turn his questions into a book, and he did, classifying them on a scale of “Light” to “Heavy” based on how serious or easygoing each question is. Once the manuscript was finished, he spent about a year querying on it. He received a lot of encouragement but no offers, and started thinking about alternative routes to reaching a readership.

Question of the Day began life as a simple, workplace pastime. Al would pose a question to co-workers, providing fodder for discussion. Eventually someone suggested Al turn his questions into a book, and he did, classifying them on a scale of “Light” to “Heavy” based on how serious or easygoing each question is. Once the manuscript was finished, he spent about a year querying on it. He received a lot of encouragement but no offers, and started thinking about alternative routes to reaching a readership.